Carbon Farming

Who’s storing it? How and Why?

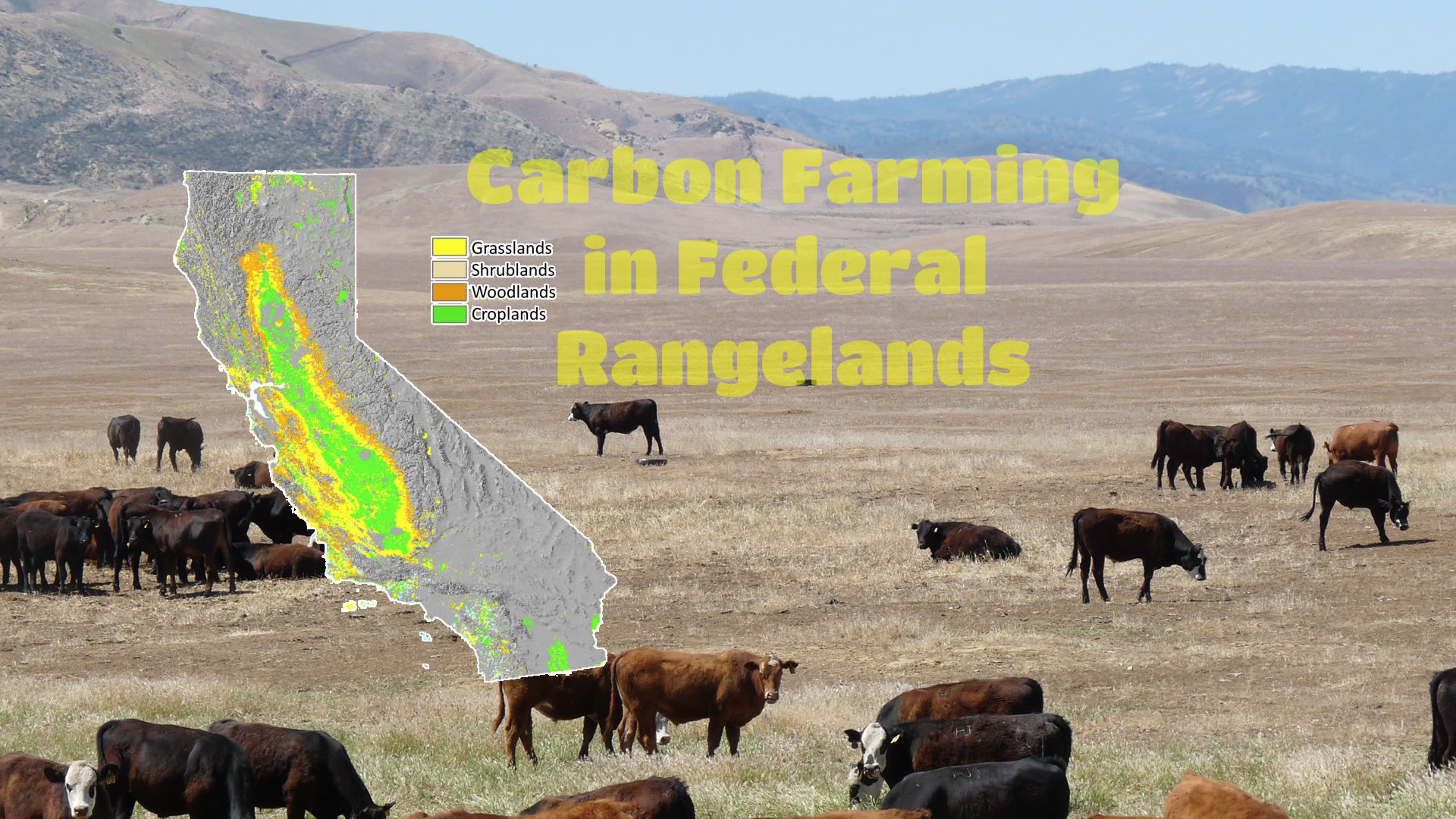

Carbon farming is the concept of storing carbon in areas with degraded soils. Rangelands with degraded soils are prime candidate spaces for carbon farming. Essentially, the pool of sequestered carbon is below the expected amount in degraded rangeland. Adding even a thin layer of compost essentially provides nutrients and soil tilth that encourages new plant growth. Plant growth increases carbon sequestration in the plant layer, humus layer and other layers of soil strata.

There are carbon farmers who are attempting to engineer plants that keep some of that carbon in the ground even longer. Carbon farming has its critics, but let’s take a deeper dive into what’s involved. Right now, it’s a concept emerging in western states. It’s happening now because climate change requires us to rethink where important resources like how compostable organics are distributed.

When looking at normal soil strata (layers in the soil) we see a number of layers.

- The vegetative layer is on top, usually accompanied by

- The humus layer, sort of brown and mulched up bits of dead plant matter. (The humus layer is where compost and mulch reside. Compost and mulch are our protagonists on this page. More on that later.) Under that we have

- The topsoil, where various grubs and worms live. Grubs and worms live in the humus as well.

- Subsoil is the next layer, composed of rough material that provides places for deeper roots to establish.

- Below that you might see a crumbly rock fragment layer, and sometimes also hard pan.

- The lowest layer we often speak about in context of gardening is bedrock, where it can be really difficult to dig.

These are typical layers discussed, but their composition, thickness and even existence can vary widely depending upon the environment and history of the soil involved. Ideal situations rarely exist. For instance, after a major change in soil arrangement (flood, fire, human construction) topsoil might be completely stripped from some areas. That’s where our heroes come in: Compost and Mulch.

Regardless of where you live, if you have access to compost, mulch, lawn-clippings, food scraps, even wood chips and a place to compost and distribute them, it’s a better alternative than simply burying these in a landfill — or worse — burning them. Due to the carbon cycle, carbon in mulch and compost is broken down in the soil and reused in new growth. We are not permanently sinking carbon into the ground. Instead, we’re basically keeping it busy in an ever turning “regreen” cycle, with the overall benefit of climate moderation and sustainability.

Some people are skeptical of the concept of carbon farming. However, it’s important to reframe before we throw shade. Here are reasons why, in some areas, carbon farming may be a fairly important consideration in regreening and environmental sustainability.

Water Climate and Legislation in the US

The United States has two general water regimes, the arid western regime and the humid eastern regime. This is borne out in the general legal structure of how water is meted out for citizens in eastern and western states. The western states (generally west of the Mississippi River) use a form of water law called “prior appropriation” which is basically like a mining claim. Whomever makes appropriate use of the water first gets first rights. However, if you live next to the same water source but you don’t have the appropriate legal claim, you can’t use the water. This legal structure may be appropriate for an arid climate, especially considering that copious water needs to remain available for indigenous flora and fauna. The eastern states have a water legal structure called “Riparian Rights” which basically comes direct from old English common law that says “If you live adjacent to a body of water, you have the right to make reasonable use of the water.” Water is more abundant in the east than it is in the west, so this legal structure for water seems to work best there.

Where water is abundant, carbon farming may not seem appropriate because with the water comes a host of normal bacteria, fungi and soil fauna that quickly break down just about anything made of dead plant matter. But guess what? You’re still going to compost and mulch because it’s an excellent way to maintain and sustain an existing landscape, especially in urbanized areas to maintain soil resilience and to reduce the heat-island effect.

In the western arid areas, we’ve begun to experience more heat and extended drought, probably due to a number of human-introduced factors that are too numerous and thorny to get into here. Regardless, the end result is that according to Kevin Drew (one of our COOLNow advisors), in a lot of places in the west, due to all the fires, drought and heat, the soils are going gray. They are losing their sustainable humus layer, and in some cases even top soil is going away. We have to start somewhere. If that means putting down compost and mulch on barren soils, that’s a start. It may just stay there until the next rain which might not be for years. But when it does rain, that means the soil will be more likely to retain that water due to the compost or mulch applied to the soil. With continued maintenance of mulch over large swaths of barren soils, at some point, plant life will encroach and emerge, beginning and hopefully maintaining a sustainable carbon cycle once again.

Whether you live east or west, if you live in a mostly suburban/urban setting, diverting organic compostables and mulch from landfills and diverting from burning may be the only way to bring back more sustainable climate in arid areas that have edged past the realm of sustainability. If you ask any gardener or farmer, you’ll find it’s also a cheap and accessible way to maintain existing landscapes where humid, resilient soils already exist.

Carbon Farming vs Carbon Sequestration – What’s the difference?

In the case of simply amending soil with compost or mulch, we can’t make the claim that we are sequestering carbon long-term, but we are absolutely fostering resilient soils and moderated climates by maintaining a cycle of regreening. We’re keeping that carbon busy. Plant-based carbon sequestration may be a welcome goal of some carbon farmers if the science can bring it about with bioengineered plants, but until all the facts are in and long-term plant-based carbon sequestration is proven plausible, soil resilience and climate sustainability are our main drivers for applying compost and mulch to our soils. In the same way we have animal husbandry, think of carbon farming as soil husbandry.

More information

Thanks to Kevin Drew for his perspectives on Carbon Farming!

Check out these links for more information:

An article at Bioneers with video about the Marin Carbon Project

An article in the Atlantic questioning a techno-plant carbon sequestration method that is also considered a form of carbon farming.

California’s Healthy Soils Initiative

Zero Foodprint (ZFP) – food businesses and their customers help farmers turn bad carbon into good carbon.